Mapping Cultures

In today's interconnected world, it is becoming increasingly common to work or collaborate with people from across the world. Being faced with that, have you ever found yourself thinking things like, “wow, these [insert people of a certain country] are so [rude / direct / rigid / duplicitous / lazy / late / etc]”? To a various extent, many people fall for this kind of stereotyping, but not so many take the time to understand the reason for such differences - in fact, this is the key: people from the various cultures in our world are different and think differently, and how this came to be had to do with a multitude of variables including history, geopolitics, language, religion and others. But different doesn't mean inferior or superior, so it becomes important to understand those differences.

When did this become a “thing”?

Cross-cultural behavior and communication have been relatively recent objects of study, with most of the meaningful research in this field taking place only in the last 60 years or so. One of the early pioneers of intercultural communication was Edward T. Hall, who is considered the founding father of this field. He created concepts such as low-context and high-context cultures (discussed below) and studied the different cultural approach to time and space.

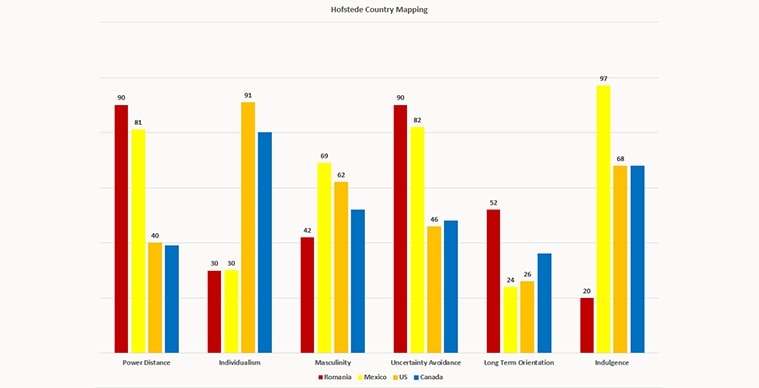

One of the first major studies of culture across multiple countries was conducted and released in 1980 by Geert Hofstede who use it to develop a model mapping country culture across four dimensions, introducing important concepts such as power distance. Otherresearchers further expanded in field in subsequent years, proposing different models.

The latest cultural model

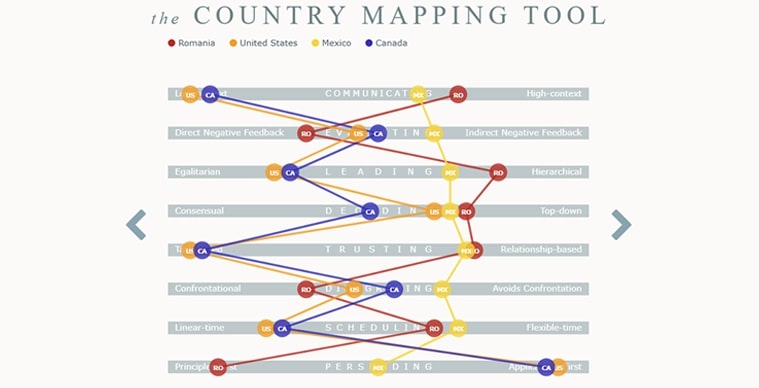

More recently, Erin Meyer, a professor at INSEAD specialized in cross-cultural communication, has developed a model which maps country cultures across 8 dimensions / axes, focused primarily on a business communication perspective. Reading Erin Meyer's book - “The Culture Map: Decoding How People Think, Lead and Get Things Done Across Cultures” has been a very interesting experience and has provided multiple “aha!” moments - I would highly recommend it to anyone working closely with one or more foreign cultures. The rest of this article will refer to Meyer's and Hofstede's cultural dimensions and will apply their models to map the different national cultures that are currently a part of Amber (Romania, US, Mexico and Canada), with some explanations and comments on the differences between the various cultures involved and their impact on our multi-cultural organization.

Culture Models

Building on previous research, Erin Meyer proposes 8 dimensions for mapping culture, including some being used in previous models as well. The dimensions are presented briefly during the book's introductory chapter, after starting with two examples that do a good job of illustrating the problem of cultural misunderstanding in business settings. They are listed below (direct quote, Chapter 1):

- Communicating: low-context vs. high-context;

- Evaluating: direct negative feedback vs. indirect negative feedback;

- Persuading: principles-first vs. applications-first;

- Leading: egalitarian vs. hierarchical;

- Deciding: consensual vs. top-down;

- Trusting: task-based vs. relationship-based;

- Disagreeing: confrontational vs. avoids confrontation;

- Scheduling: linear-time vs. flexible-time.

What is important is to understand that the cultural differences become apparent and can be explained with the map only when compared to other countries. For example, Mexico appears on the right side of the Trusting scale and seems to be generally a relationship-oriented country, but only if compared to countries such as US or Canada, which appear towards the left side. On the other hand, for someone from an Asian country (India or Vietnam, for example), the average Mexican person will appear to be rather task oriented.

Other important aspect is that personality and individual culture also have an impact. For countries which are close to each other on the scale, their distributions will overlap. So, looking at the same example, different behavior between an American and a Canadian person on the Trusting scale will have more to do with their individual culture rather than their respective country cultures.

Hofstede's model

Let's also take a look at the model proposed by Hofstede. His model initially included 4 dimensions, with 2 more being added later on. Hofstede's model assigns scores to each dimension and is simpler to interpret. The dimensions used by this model area:

- Power Distance

- Individualism

- Masculinity

- Uncertainty Avoidance

- Long Term Orientation

- Indulgence

Armed with these tools, let's have a look at the practical implications within Amber.

Fig. 1: Erin Meyer culture mapping for Romania, Mexico, US and Canada

Fig. 2: Hofstede culture model figures for Romania, Mexico, US and Canada

Amber Cultural Mapping

The communication style is quite different between US & CA on one hand, and MX and RO on the other. In brief, low-context means conveying messages using simple, direct and explicit means, sometimes repeating the other person's words to ensure the message has been received correctly, summarizing conclusions, and so on. Low-context cultures tend to say directly what they mean, generally leaving little room for misunderstandings and not focusing much on subtext. On the contrary, high-context communication assumes the other person shares a similar cultural background and uses subtle cues and references, leaving certain things to be understood without being explicitly said or sometimes communicating with a hidden meaning.

However, the rise of multinational organizations and the previous experience of Amber's staff in such companies (the large majority of Amber employees have worked in multinational companies before joining) make this less of an issue than it would seem. Generally speaking, the best way to mitigate the communication gap with multi-cultural environments is to use low-context communication whenever possible. The differences on this scale would become more evident if someone from the US were to move to Romania or Mexico, for example.

Negative feedback and disagreement

On the other hand, conveying feedback (including negative feedback) is part of day-to-day professional operations. The Evaluating scale on the Meyer model can sometimes feel rather counterintuitive. We find an immediate such example with Americans, who despite having a reputation for direct communication, when it comes to negative feedback the message is much more softened (including rules such as “3 positive messages for every negative message”). The reverse can also be found, with subtle, high-context cultures offering quite direct negative feedback. From our group, Romania is the most direct culture and Mexico the most indirect, with US & CA grouped in the middle. This dimension is very tightly correlated to the Disagreeing (confrontational) dimension as well. This explains why Romanians are sometimes perceived as aggressive or feisty in their communication and should be mindful of this important cultural difference, especially when conveying negative feedback to Mexican team members. For Americans and Canadians, it's important to keep in mind that the approach they take when confronting or communicating negative feedback may need to be quite different when dealing with Romanians compared to Mexicans.

Here's an example that illustrates the above: one of the members of Amber's Mexican leadership team received a notification from the Romanian HQ that his marketing budget would be significantly cut. The notification was sent in a rather dry email which included other company executives. There was no answer or formal acknowledgement for several days, until the Marketing group leader in Romania learned indirectly that the Mexican team was upset and disagreed with the decision. What happened was that, to the Romanian executive it seemed enough to explain the decision rationally and communicate it directly, with several stakeholders involved, for transparency. But for the Mexican director, although he accepted the decision, it felt unjust but also uncomfortable to confront the Romanian leader in a group environment. After a one-on-one conversation between the Romanian and Mexican leaders, the situation was resolved and the conflict defused.

Leadership and decision-making

On the Leadership dimension, we find again a wide difference between the US/CA and RO/MX groups. This is important to keep in mind, especially for American managers, as hierarchical cultures will tend to trust and defer to the boss, especially when in a group setting. It may sometimes be challenging for US managers to lead their international team members in an “egalitarian” way. Highly hierarchical cultures may have difficulty understanding why responsibility is pushed towards them (“isn't it the leader's job to lead?”) or to express opinions - especially in a group setting - which contradict the boss. As recommendations, it is important to have 1-on-1 discussions with team members, which may sometimes reveal information that would not be disclosed in a larger group. Sometimes it may also be useful for the egalitarian manager to have the team discuss solutions for problems without him/her and only discuss the conclusions as a group. As a side note, we see the same kind of relationship between the two groups of countries with the Power Distance parameter on the Hofstede model, which further validates these conclusions.

When it comes to making decisions, one would be tempted to think that egalitarian leadership implies consensus-based decisions and that hierarchical leadership always decides top-down. There are exceptions, however, and the Deciding scale provides an explanation for those situations. An effect of this scale is reflected in how rigid cultures are on the concept of “decision”. Consensus-building cultures may take long times for discussion and analysis of the problem, before committing to a decision they can all get behind and then that decision becomes a very powerful anchor. On the other hand, top-down decisions tend to be taken quicker and are more prone to changes. Fortunately, on the Deciding dimension the Amber cultures are much closer to each other, generally favoring a top-down approach. In hindsight, this compatibility has likely had an impact on how the company has operated in the past, allowing a large degree of efficiency and adaptability.

The way we trust and persuade

The Trusting scale presents one of the largest cultural gaps on Amber's mapping, which is important because trust is an essential value for the long-term success of any organization. US & CA are among the most task-based cultures in the world, which means they are masters of separating personal and professional relationships. To them, Mexicans and Romanians may seem more distant or even cold (especially the latter), but the truth is they approach trust in a profoundly different way. It is well worth the time for any member of the organization to invest effort into building relationships with their peers, team members and managers.

On the Persuading scale we see another major gap, especially between Romania and US/CA. In hindsight, there are many anecdotal examples in the company, with Romanian staff presenting a concept and starting with the underlying principles and explanations, only to have an American team member jump in to ask, “what's the purpose of this?”; or the other way around, for an American to present the benefits of a new process while Romanian peers would be baffled about how the new process was conceived or that nobody has thought of the ramifying implications. The takeaway, again, is to be mindful of this cultural aspect when presenting new concepts or proposing new processes.

Conclusions

As we get to the end of this article, the main point to take away is to acknowledge that these differences in national cultures exist. Being mindful of these is the first step towards trying to understand how to navigate a multi-cultural environment in today's professional world.

None of the cultural models currently available perfectly capture the intricacies of national cultures and their interactions, but they provide useful tools for illustrating why cultural clashes occur and how they can be avoided or mitigated. The models used in this article complete each other and they can be used to understand different aspects of cultures and offer perspectives on things to be mindful for when interacting with foreigners.

Game development is very much a global industry by its nature; even a small studio founded by, let’s say, Romanian developers can sign a publishing deal with a French company or hire a remote programmer from Germany. It is becoming increasingly important to be aware of the differences between cultures, and being able to navigate these can be a recipe for success.

Armed with these tools, let's have a look at the practical implications within Amber.

References

Erin Meyer, The Culture Map: Decoding How People Think, Lead, And Get Things Done Across Cultures